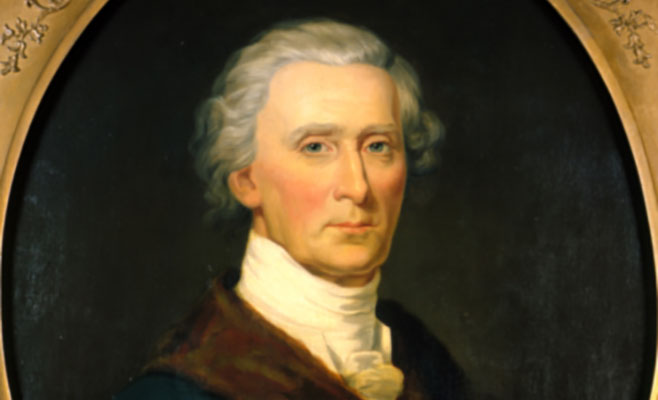

Charles Carroll

Fourteenth Sunday Year B:

Charles Carroll & the Declaration of Independence

Fr. Dwight P. Campbell, S.T.D.

This Sunday, July 4, our nation celebrates the Declaration of Independence from England by the original 13 colonies, which is seen by many as the founding of our nation.

A few years back I read a book by Michael Medved called The American Miracle, in which he describes a whole series of amazing events which demonstrate that the hand of God was at work in the founding of our nation; among these: winning critical military battles against insurmountable odds.

For example, at the Battle of New Orleans on Jan. 8 1815, a miraculous fog helped U.S. troops under Gen. Andrew Jackson to a resounding victory over the highly trained British troops that greatly outnumbered the Americans.

Ursuline nuns had been praying a novena to Our Lady of Prompt Succor, and after the battle Gen. Jackson thanked them. A thanksgiving Mass is still celebrated by the Archbishop of New Orleans every year Jan. 8 at the national shrine of Our Lady of Prompt Succor.

Another interesting fact that Michael Medved points out concerns two of the signers of the Declaration of Independence: Thomas Jefferson, who penned that document and became our third President; and John Adams, who was our second President.

Both men died on July 4, 1826 – the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Both men died within five hours of each other, though without knowledge of the other’s death. Coincidence? Or, God’s Providence at work? About a month later Daniel Webster commented on the death of these two founders on the same day, saying that it was “proof that our country and its benefactors are objects of [God’s] care.”

There was one lone the Catholic who signed the Declaration of Independence: Charles Carroll, who died in 1832 at the age of 95, as the last surviving signer of that document. Charles Carroll was born to Irish parents in 1737 in Annapolis, Maryland. At age 11 he was sent to France where he was educated first by the Jesuits, and later obtained a law degree in London before returning to Annapolis and 1765.

He was fluent in five languages, and had received the most extensive formal education of any of the signers of the Declaration.

But at that time, being a Catholic was difficult because Catholics were subject to unjust discrimination. For example Catholics were barred from holding public office in Maryland, due to a law passed in 1704 to “prevent the growth of popery in his province.”

One can say that this law was doubly unjust, considering that Maryland was founded as a Catholic colony, and the original Catholic colonists there practiced tolerance toward people of other faiths, which tolerance was not reciprocated after the Protestants became the majority in that colony.

Our Gospel today from St. Mark relates that when Jesus returned to His native place (Nazareth) to preach, He was not accepted; in fact, those who had known Him when He was growing up there “took offense at him” (it’s seems that they envied Him); and this caused Jesus to say, “a prophet is not without honor except in his native place and among his own kin and in his own house” – and that Jesus “was not able to perform any mighty deed there, apart from curing a few sick people. He was amazed at their lack of faith.”

We must note that when St. Mark tells us that Jesus “was not able to perform any mighty deed [miracle] there,” he does not mean that Jesus lacked the power to do so; rather, He refused to do so because they did not deserve miracles on account of their lack of faith in Him.

But back to our story. Just as Jesus was rejected in his native place, so was Charles Carroll. In Maryland, his native place, he could not earn a living as an attorney or hold public office precisely because he was Catholic.

Beginning in 1765, the year Charles Carroll returned to Maryland, the British began taxing the colonists. Charles became a prominent voice in opposing this injustice, arguing that the colonists should be able to control their own taxes.

Years after he signed the Declaration of Independence, Charles Carroll remarked: “I zealously entered into the Revolution” in order to obtain religious as well as civil liberty”; “God grant that this religious liberty may be preserved in these states, to the end of time, and that all who believe in the religion of Christ may practice the leading principle of charity, the basis of every virtue.”

Charles Carroll was a man of considerable wealth, who owned a much property, and helped to finance the revolution. He helped to establish religious freedom for all Catholics in the years after our nation was founded.

Charles himself was chosen to attend the Continental Congress in 1776; and in 1781 he was elected to the Maryland State Senate, a post he held until 1800. He also helped to found the first Catholic diocese in the United States, which became the Archdiocese of Baltimore. His cousin, John Carroll, was appointed the first Bishop of Baltimore.

In the first part of the 1800’s, a Frenchman named Alexis de Tocqueville toured this new nation, the United States of America, and wrote his reflections in a famous book called Democracy in America. In this work he said:

“Not until I went into the churches of America and heard the pulpits flame with righteousness did I understand the greatness and genius of America. America is great because America is good. If America ever ceases to be good, America will cease to be great.”

Our first president, George Washington, likewise acknowledged that morality is necessary for true democracy to flourish and bring happiness to people:

“Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism, who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens.”

John Adams uttered similar words: “Religion and virtue are the only foundations for free government.”

Finally, James Madison, our nation’s fourth president, said: “The future of America rests not in the laws of this Constitution, but in the laws of God.”

Let us pray, on this anniversary of the signing of our nation’s founding document: May the people in our country return to God and to the practice of Christian morality; may our laws and policies reflect the laws of God and the teachings of Christ and His Church, so that our nation may be worthy to have Christ, the King of kings and the Lord of lords, reign over it, and that God may bestow His blessings upon it – now, and to the end of time.

* Information in this homily was taken from an article by Dr. Donald DeMarco, “The Lone Catholic Signer of The Declaration of Independence,” in The Wanderer (July 1, 2021), 4A (www.thewanderer press.com)